Turning readers to locally published English-language books

"is a difficult, if not downright thankless, job", says

The Star, which ran a story about a publishing symposium in Singapore and why things are tough for locally published English books.

Linda Tan Lingard, of the Yusof Gajah Lingard Literary Agency, told

The Star: "Locally-published books in English face fierce competition from imported titles."

Oon Yeoh, senior consulting editor at MPH Group Publishing, also put in his two sen:

...local long-form fiction in English doesn't do very well. "Non-fiction books, such as 'how-to' books and cookbooks, tend to do better than fiction, though short story collections sometimes do well."

He added that the price point for locally-published books needs to be lower as well. "Imported titles sell even when they are priced well over RM50, for instance. With local books, however, the buying public is not prepared to spend more than RM50."

So, why are imported foreign English-language titles - some of which do cost more than RM50 - seem more popular among Malaysians than local stuff?

Raman Krishnan of Silverfish Books, who

The Star also interviewed, said:

"Anglo/American books are sucking the air out of the Malaysian and Singaporean publishing industries, he said. "In Malaysia, the distributor decides what books the public reads, which in turn is decided by media reports from the West."

He believes the key is in building "a healthy local and regional market". But who's going to put out for that? Will bookstores be willing to invest, when they seem to be more focused on the bottom line than home-grown bylines?

Who really decides?

However, someone from a major books distributor told me it's the reading public who decides what the bookstores sell, based on what's popular with them.

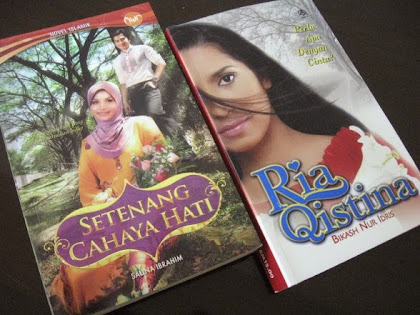

The usual suspects include the Anglo/American stuff, as well as Malay romance, horror, religion and romance-religion (what). And, as my esteemed colleague puts it, the "'how-to' books and cookbooks".

That might be true for the big chains, who depend on shifting as many "hot" items as possible to stay afloat. And if many of their customers are from the middle to upper class, the bit about the Western media's influence in shaping consumption habits sounds plausible - not just for books, but film as well - because, as we know, only that strata of society are more likely to be able to read and have access to that kind of material.

So local writing ends up in what would be considered niches, dismissed as "arty", "fringe", "experimental" - euphemisms for "risky", "unprofitable" and the like in big bookselling.

The Anglo yardstick introduces other problems as well. Nigeria-based author Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, author of the award-winning

I Do Not Come to You by Chance, laid out the problems African authors have in getting noticed (as well as other challenges). In

The New York Times, she says African literature is beginning to receive recognition outside the so-called Dark Continent.

The catch?

...we are telling only the stories that foreigners allow us to tell. Publishers in New York and London decide which of us to offer contracts ... American and British judges decide which of us to award accolades ... Apart from South Africa, where some of the Big Five publishers have local branches, the few traditional publishers in Africa tend to prefer buying rights to books that have already sold in the West, instead of risking their meager funds by investing in unknown local talents.

Nope, these African voices, like Nwaubani's, do not come to us by chance.

As a result, she says, most authors in her home country are self-published. But "with no solid infrastructure for marketing and distribution" and the clout that comes with winning international awards:

...the success of these authors' works is often dependent on how many friends, family members and political associates can attend their book launches and pay exorbitant prices for each copy. Or on whether they have a connection in government who can include their book as a recommended text for schools.

Sounds familiar?

Social engineering? Or slow suicide?

I see parallels in the whole "our readers want us to sell these books" with what outgoing ESPN ombudsman Robert Lipsyte

seemed to suggest about the sports channel not doing heavy hitting journalism because, according to

Slate, "the viewers don't want them to".

"Extensive investigative reporting into the exploitation of college athletes, and the legal battles around that, would seem to conflict with ESPN’s business model," he wrote in his last column. By "business model", I think he means the near-deification of the nation's sports stars.

I'm not sure what kind of myth the big publishers want to foist on the world. That what they publish is all that matters? Can it be as simple as pushing what they deem to be "the thing" while making money out of it?

If that's true, the big publishers' preference and obsession for the next big thing, something

The Globe and Mail calls

"blockbustering", might spell their doom:

As they grow larger and concentrate their efforts and investments on massive, sure-fire hits ... the cultural landscape seems paradoxically smaller. It becomes even more difficult to get an indie film made – the huge projects suck the oxygen (financing, distribution, media coverage) out of the biosphere (hey, same terminology as Raman's).

In following this larger trend, book publishers are shortsighted. By reducing their involvement in original and challenging art, they relinquish literary fiction to the tiny presses and online magazines, and so become artistically irrelevant and, in the long run, uninteresting even as suppliers of entertainment. Pursuing mainstream popularity with ever-larger sums of money is ultimately self-destructive.

Reversing this trend sounds simple: don't do all that! But will they listen?

Market writers, not what's written

Now, how to start building Raman's local market? "Don't sell books, sell personalities," he told

The Star (and everyone else) "Sell the writers."

That would work, considering how

kepochi (busybody-ish) Malaysians tend to be. Even if their short-term goal is trying to find out how to be a best-selling author themselves.

Besides, books don't sell themselves. They need to be marketed; the difference is in the degree of marketing. I'm sure even the publisher for

Fifty Shades had to tell people "Kinky stuff here!"

Others have had to work real hard. Appearances at book fairs, literary festivals, book tours and signings, media interviews, the whole shebang. The writers who've made it, the names that seem to jump off the shelves, didn't they put in the hours when they first started?

Some of them still tour and perform. Brand names that don't maintain themselves fade away - at least until they start asking "Don't you remember me?"

Examples closer to home include

the author of a successful series of autobiographical stories in cartoon format, who has built such a rapport with fans, his books are still selling today;

a writer who I heard hawked her crime novel overseas and picked up a deal with a major international publisher; a

cycling enthusiast and activist who takes her book about her travels on the road with her; and that

best-selling "housewife" who came up with lots of ideas to spread the word about her works.

But again: will bookstores and publishing houses put out, if the authors are up for it - even if they're not famous or established? And, authors: will some of you have the fortitude to swallow your pride and work with the suits to shift the copies?

Reading ahead

An incident about a novel also

made me think about the future face of publishing and publishers - as well as marketing and criticism.

The guys with all the passion, they start off small. Once they get big, they are likely to end up swim in bigger oceans where there's LOTS of competition - and spend much of their time just surviving, rather than putting in the hours enlightening the masses and enriching the pool of literature. This eventually sucks them dry of all the love of words and bookselling, leaving them mere shells of the former selves.

Maybe the answer doesn't lie in big but in small, as eloquently put in

this piece about the 2014 George Town Literary Festival. Staying small might mean a smaller reach and support base, but it also means more time and effort is spent to fulfil The Purpose, rather than continually fighting for survival.